Leukoplakia of the oral cavity: causes of the disease

The reasons causing the development of the disease include:

- Smoking. When using tobacco, the oral cavity is exposed to various irritants, including thermal (incoming smoke has a temperature of about 60 degrees Celsius) and chemical (nicotine, tar and combustion products). No less dangerous is chewing tobacco, which is also a provoking factor.

- Eating either very hot or very cold food on a regular basis for a long time.

- Mechanical trauma (bad bite, sharp edges of teeth, orthopedic structures installed with violations).

- Metal seals that cause galvanic currents.

- Inhalation of vapors of gasoline, benzene, varnishes and paints, as well as other resins.

- Hormonal imbalance, constant stress and lack of retinol.

Symptoms

The first signs of the disease often go unnoticed because they do not cause any pain or discomfort in the patient. Nevertheless, a specialist will be able to determine the onset of leukoplakia by the appearance of the mucous membrane, lips and the area where the teeth meet.

The first sign of the disease is the appearance of a keratinized gray area, which can appear on the palate (in smokers), in the corners of the mouth, on the inside of the cheek, etc. An easily removable white plaque forms in this area, but after a few days the formation makes itself felt again . The patient may feel tightness in the mouth, but, as practice shows, most people simply do not pay attention to this.

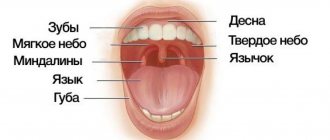

Plaques with a diameter of no more than 4 centimeters are formed. They may appear:

- on the inner surface of the cheeks;

- on the tongue (on the back or sides);

- in the sky;

- on the gums;

- in the corners of the mouth.

The process of plaque formation takes up to one month. At the first stage, the area of the future formation seems slightly swollen; when you feel it with your fingers, the compaction is not felt. However, over time, another symptom of oral leukoplakia appears - the mucous membrane at the site of the swelling loses its original shine and becomes rough, which is noticeable when touched.

There is no pain in this case: only sometimes a feeling of dryness at the site of the outbreak is possible.

Gradually, the color of the spots changes from gray to bright white. The spots in most cases have clear boundaries. Their increase is possible when the disease enters its second stage, called verrucous.

The disease often causes candidiasis and malignant cancers. In an advanced state, leukoplakia is very difficult to treat: the affected areas become even more keratinized, ulcers can form, and the infection gradually spreads to other areas of the mouth.

1.General information

The oral mucosa is characterized by a number of distinctive features.

It is located in close proximity to vital organs, endocrine glands, lymph nodes; serves as a covering for the “entry gate” for the digestive tract and respiratory tract; it is intensively innervated, supplied with blood, moisturized, and renewed very quickly. Therefore, this mucous layer, extremely sensitive to any physiological, hormonal, biochemical changes in the body, can serve as a reliable early indicator of a pathological process, which sometimes begins in a completely different zone and system. Moreover, it is specific changes in the oral mucosa, discovered, for example, during a dental examination or treatment, that often turn out to be the first and at that time the only sign of a particular disease, sometimes formidable and severe, but progressing asymptomatically until a certain stage.

A must read! Help with treatment and hospitalization!

Kinds

- The most common is simple or, as it is also called, flat leukoplakia . It is usually discovered by chance during an examination by a dentist, since the patient does not experience any subjective sensations. A burning sensation occurs extremely rarely, and the appearance of the mucous membrane may change. If the disease affects the tongue, loss of taste may occur.

- Hairy leukoplakia of the tongue resembles stomatitis. The shape of the spot that appears, as well as its size, can be different, the color - from pale gray to white. The surface of the mucous membrane at the site of the lesion becomes slightly rough, which can be felt to the touch. On the cheeks it appears as solid or broken lines. It can also be found on the lips, where it looks like thin paper pasted on.

- Verrucous leukoplakia is the second stage of the development of the disease. The keratinization thickens, the affected area seems to rise above the nearby tissues. When you touch it with your fingers, you feel a compaction.

- Erosive form . Untimely diagnosis of the two previous stages of the disease leads to a worsening of the situation - the person feels pain when exposed to any irritants, erosions or ulcers are visible in the mouth.

- Soft leukoplakia is a type of cancer. Its distinctive feature is peeling of tissue in the area of the lesion. To clarify the diagnosis, a histological method of studying cells is required.

- Tappeiner's leukoplakia . This form of the disease affects people who abuse smoking. According to studies, daily smoking 10 cigarettes a day increases the chance of developing the disease by 50 times (as the number of cigarettes increases, the risk also increases)

The disease begins with the formation of lesions on the roof of the mouth (sometimes they appear on the gums). The mucous membrane changes its color to a pronounced gray or bluish, which is noticeable to the naked eye, folds appear on it. Reddish nodules may begin to appear, which is accompanied by infectious inflammation of the oral cavity (caused by the accumulation of salivary gland secretions in the tissues).

Stomach

Stomach

(lat.

ventriculus

) - a section of the digestive tract following the esophagus and preceding the duodenum. Upon examination, the position, size, and shape of the stomach depend on the position of the patient, the filling of the stomach, as well as on the condition of the surrounding organs - the liver, spleen, and intestines. The stomach, 5/6 of its size, lies to the left of the midline and only the pyloric part lies to the right.

The upper part of the stomach, being a continuation of the esophagus, is tightly fixed to the diaphragm by connective tissue cords. The entrance to the stomach (cardia) is located 3 cm from the place of attachment of the VII left costal cartilage to the sternum or at the level of the X-XI thoracic vertebra in the back. The highest point of the gastric vault lies on the fifth rib on the left along the parasternal line. The greater curvature, as the most mobile part of the stomach, is located more in front, adjacent, together with part of the anterior surface of the stomach, to the anterior abdominal wall. On the left, the upper part of the greater curvature touches the spleen, and the lower part touches the transverse colon.

The level of the lower edge of the greater curvature is very variable and depends on the type of constitution, gender, position of the patient (horizontal, vertical), the size of the abdomen, the tone and filling of the stomach. In women it is 1-2 cm lower than in men. In a horizontal position of the patient with an average filling of the stomach, it is located 2-3 cm above the navel in men, at the level of the navel in women, and when the stomach is full, the level drops lower. In the vertical position of the subject, the lower edge of the stomach in men is 3-4 cm, in women - 2-3 cm above the iliac line. The swollen and overcrowded transverse colon pushes the greater curvature from the anterior abdominal wall backward and upward. The outlet of the stomach is located at the level of the first lumbar vertebra, 1-2 cm to the right of the midline (Ionov A.Yu. et al.).

The normal residence time of the contents (digested food) in the stomach is about 1 hour.

Anatomy of the stomach

Anatomically, the stomach is divided into four parts:

- cardiac

(lat.

pars cardiaca

), adjacent to the esophagus; - pyloric

or pyloric (lat.

pars pylorica

), adjacent to the duodenum; - body of the stomach

(lat.

corpus ventriculi

), located between the cardiac and pyloric parts; - fundus of the stomach

(lat.

fundus ventriculi

), located above and to the left of the cardiac part.

In the pyloric section there is a pyloric cave

(lat.

antrum pyloricum

), synonyms

antrum

or

anturm

and

pyloric

(lat.

canalis pyloricus

).

The figure on the right shows: 1. Body of the stomach. 2. Fundus of the stomach. 3. Anterior wall of the stomach. 4. Greater curvature. 5. Small curvature. 6. Lower esophageal sphincter (cardia). 9. Pyloric sphincter. 10. Antrum. 11. Pyloric canal. 12. Corner cut. 13. A groove formed during digestion between the longitudinal folds of the mucosa along the lesser curvature. 14. Folds of the mucous membrane.

The following anatomical structures are also distinguished in the stomach:

- anterior wall of the stomach

(lat.

paries anterior

); - posterior wall of the stomach

(lat.

paries posterior

); - lesser curvature of the stomach

(lat.

curvatura ventriculi minor

); - greater curvature of the stomach

(lat.

curvatura ventriculi major

).

The stomach is separated from the esophagus by the lower esophageal sphincter and from the duodenum by the pyloric sphincter.

The shape of the stomach depends on the position of the body, the fullness of food, and the functional state of the person. With average filling, the length of the stomach is 14–30 cm, width 10–16 cm, length of the lesser curvature 10.5 cm, greater curvature 32–64 cm, wall thickness in the cardiac region 2–3 mm (up to 6 mm), in the antrum 3 –4 mm (up to 8 mm). The stomach capacity is from 1.5 to 2.5 liters (the male stomach is larger than the female). The normal weight of the stomach of a “conditional person” (with a body weight of 70 kg) is 150 g.

The stomach wall consists of four main layers (listed from the inner surface of the wall to the outer):

- mucous membrane covered with single-layer columnar epithelium

- submucosa

- muscle layer, consisting of three sublayers of smooth muscle:

- inner sublayer of oblique muscles

- middle sublayer of circular muscles

- outer sublayer of longitudinal muscles

Between the submucosal base and the muscular layer there is a nervous Meissner (synonym submucosal; lat. plexus submucosus

) plexus, which regulates the secretory function of epithelial cells, between the circular and longitudinal muscles - Auerbach (synonym intermuscular; lat.

plexus myentericus

) plexus.

Lectures for medical university students (video)

Lecture for students of the medical university “Ulcers of the stomach and duodenum” by Professor Yu.T. Tsukanova, in which he touches on the anatomy of the stomach and talks about its mucous membrane

Still from a video lecture by Dr. O.S. Tarasova “Physiology of Digestion” for students at the Faculty of Bioengineering and Bioinformatics of Moscow State University. M.V. Lomonosov

Frame “Stomach in children” from a video lecture by Ph.D. Gostishchevoy E.V. Anatomical and physiological features of the digestive organs in children. Methods and methods for studying the digestive system in children

Still from a video lecture by Lebedev A.V. Acid-dependent diseases of the gastrointestinal tract

Still from a video lecture by Abdiev G.Kh. Surgical diseases of the stomach and duodenum

Stomach mucosa

The mucous membrane of the stomach is formed by a single layer of columnar epithelium, a layer of its own and a muscular plate that forms folds (relief of the mucous membrane), gastric fields and gastric pits, where the excretory ducts of the gastric glands are localized.

In the proper layer of the mucous membrane there are tubular gastric glands, consisting of parietal cells that produce hydrochloric acid; main cells producing the proenzyme pepsin pepsinogen, and accessory (mucosal) cells secreting mucus. In addition, mucus is synthesized by mucous cells located in the layer of the surface (integumentary) epithelium of the stomach. The surface of the gastric mucosa is covered with a continuous thin layer of mucous gel consisting of glycoproteins, and underneath is a layer of bicarbonates adjacent to the superficial epithelium of the mucosa. Together they form the mucobicarbonate barrier of the stomach, which protects epithelial cells from the aggression of the acid-peptic factor (Y.S. Zimmerman). The mucus contains antimicrobial activity immunoglobulin A (IgA), lysozyme, lactoferrin and other components.

The surface of the mucous membrane of the body of the stomach has a pitted structure (see figure on the left, Matveeva L.V. et al.), which creates conditions for minimal contact of the epithelium with the aggressive intracavitary environment of the stomach, which is also facilitated by a thick layer of mucous gel. Therefore, the acidity on the surface of the epithelium is close to neutral. The mucous membrane of the body of the stomach is characterized by a relatively short path for the movement of hydrochloric acid from the parietal cells into the lumen of the stomach, since they are located mainly in the upper half of the glands, and the main cells are in the basal part. An important contribution to the mechanism of protecting the gastric mucosa from the aggression of gastric juice is made by the extremely rapid nature of gland secretion, caused by the work of the muscle fibers of the gastric mucosa. On the contrary, the mucous membrane of the antral region of the stomach (see the figure on the right) is characterized by a “villous” structure of the surface of the mucous membrane, which is formed by short villi or convoluted ridges 125–350 µm high (Lysikov Yu.A. et al.).

Still from video by Partsvania-Vinogradova E.V. The role of pH-metry in acid-related diseases

Stomach in children

In children, the shape of the stomach is not constant and depends on the constitution of the child’s body, age and diet.

In newborns, the stomach has a round shape; by the beginning of the first year it becomes oblong. By the age of 7–11, a child’s stomach does not differ in shape from an adult’s. In infants, the stomach is positioned horizontally, but as soon as the child begins to walk, it takes on a more vertical position. By the birth of a child, the fundus and cardiac part of the stomach are not sufficiently developed, and the pyloric part is much better, which explains frequent regurgitation. Regurgitation is also promoted by swallowing air during sucking (aerophagia), with improper feeding technique, short frenulum of the tongue, greedy sucking, and too rapid release of milk from the mother's breast.

| Age | Stomach volume, ml |

| newborns | 30–35 |

| 1 year | 250–350 |

| 2 years | 300–400 |

| 3 years | 400–500 |

| 8 years | 1000 |

Gastric juice

The main components of gastric juice are: hydrochloric acid secreted by parietal cells, proteolytic enzymes produced by chief cells and non-proteolytic enzymes, mucus and bicarbonates (secreted by accessory cells), intrinsic Castle factor (production of parietal cells).

The gastric juice of a healthy person is practically colorless, odorless and contains a small amount of mucus.

Basal secretion, not stimulated by food or otherwise, in men is: gastric juice 80-100 ml/h, hydrochloric acid - 2.5-5.0 mmol/h, pepsin - 20-35 mg/h. Women have 25–30% less. About 2 liters of gastric juice are produced in the stomach of an adult per day.

The gastric juice of an infant contains the same components as the gastric juice of an adult: rennet, hydrochloric acid, pepsin, lipase, but their content is reduced, especially in newborns, and increases gradually. Pepsin breaks down proteins into albumins and peptones. Lipase breaks down neutral fats into fatty acids and glycerol. Rennet (the most active enzyme in infants) curdles milk (Bokonbaeva S.D. et al.).

Stomach acidity

The main contribution to the total acidity of gastric juice is made by hydrochloric acid produced by the parietal cells of the fundic glands of the stomach, located mainly in the area of the fundus and body of the stomach.

The concentration of hydrochloric acid secreted by parietal cells is the same and equal to 160 mmol/l, but the acidity of the secreted gastric juice varies due to changes in the number of functioning parietal cells and neutralization of hydrochloric acid by alkaline components of gastric juice. Normal acidity in the lumen of the body of the stomach on an empty stomach is 1.5–2.0 pH. The acidity on the surface of the epithelial layer facing the lumen of the stomach is 1.5–2.0 pH. The acidity in the depths of the epithelial layer of the stomach is about 7.0 pH. Normal acidity in the antrum of the stomach is 1.3–7.4 pH.

On the graph: 24-hour pH-gram of the body of the stomach is normal (Storonova O.A., Trukhmanov A.S.)

Currently, the only reliable method for measuring gastric acidity is considered to be intragastric pH-metry, performed using special devices - acidogastrometers, equipped with pH probes with several pH sensors, which allows you to measure acidity simultaneously in different zones of the gastrointestinal tract.

Stomach acidity in relatively healthy people (who do not have any subjective gastroenterological sensations) changes cyclically during the day. Daily fluctuations in acidity are greater in the antrum than in the body of the stomach. The main reason for such changes in acidity is the longer duration of nocturnal duodenogastric reflux (DGR) compared to daytime, which throws duodenal contents into the stomach and, thereby, reduces the acidity in the lumen of the stomach (increases pH). The table below shows the average acidity values in the antrum and body of the stomach in apparently healthy patients (Kolesnikova I.Yu., 2009):

| Index | Day | Day | Night |

| Average acidity of the stomach body, units. pH | 3,2 | 3,1 | 3,3 |

| Average acidity of the antrum of the stomach, units. pH | 4,0 | 3,6 | 4,4 |

| Number of DGRs lasting more than 5 minutes | 29 | 12 | 18 |

| Number of DGRs reaching the body of the stomach | 11 | 5 | 6 |

The general acidity of gastric juice in children of the first year of life is 2.5–3 times lower than in adults. Free hydrochloric acid is determined during breastfeeding after 1–1.5 hours, and during artificial feeding – after 2.5–3 hours after feeding. The acidity of gastric juice is subject to significant fluctuations depending on the nature and diet, and the state of the gastrointestinal tract.

Gastric motility

In terms of motor activity, the stomach can be divided into two zones: proximal (upper) and distal (lower). There are no rhythmic contractions or peristalsis in the proximal zone. The tone of this zone depends on the fullness of the stomach. When food arrives, the tone of the muscular lining of the stomach decreases and the stomach reflexively relaxes.

| Motor activity of various parts of the stomach and duodenum (Gorban V.V. et al.) |

Gastric accommodation is a postprandial vagal reflex, leading to a decrease in the tone of the stomach (primarily in the proximal section) in response to food intake (see figure on the left). Gastric accommodation provides a reservoir for ingested food without a significant increase in intragastric pressure. Esophageal distension may also be accompanied by proximal gastric relaxation. So-called adaptive relaxation involves relaxation of the proximal stomach in response to stretching of the antrum. Adaptive relaxation ensures the creation of a pressure gradient inside the organ, which promotes mixing of food and its adequate grinding. Adaptive relaxation can be generated by both local (with the initiation of mechanoreceptors in the antrum) and vago-vagal reflexes.

| Application of electrodes to the patient's abdomen during electrogastrography |

In the proximal zone in the area of the greater curvature of the stomach, interstitial cells of Cajal are located, which form the rhythm of gastric contractions (on average 3 cycles per minute).

The resulting peristaltic waves are directed towards the duodenum. Their functional role is to push the contents of the stomach towards the pylorus. The motor function of the stomach is studied using electrogastrography. It is accepted that, depending on the frequency of the fundamental harmonic, the following occurs:

- normogastria (normal motility) - at a frequency of 2 to 4 cycles per minute

- bradygastria (reduced motility) - with a frequency of less than 2 cycles per minute

- tachygastria (increased motor skills) - at a frequency of 4 to 10 per minute.

The graph shows electrogastrograms of the stomach before (red curve) and after eating (green). The abscissa axis is seconds, the ordinate axis is millivolts (Popov A.I., Rudalev A.V.).

Using electroenterogastrography (which uses the same Gastroscan-GEM device, but the research methodology differs from electrogastrography), the following gastric motility disorders are detected:

- irritable stomach

- characterized by normal or reduced electrical activity of the stomach on an empty stomach with a subsequent increase in its electrical activity after eating by more than 1.5-2 times - lazy stomach

- characterized by normal electrical activity of the stomach on an empty stomach and a decrease in it after eating - asthenic stomach

- characterized by a high level of electrical activity of the stomach on an empty stomach and a decrease in it after eating (Rachkova N.S., Khavkin A.I.).

An important role in the implementation of the motor function of the stomach in children belongs to the activity of the pylorus, thanks to the reflex periodic opening and closing of which food masses pass in small portions from the stomach to the duodenum. In the first months of life, the motor function of the stomach is poorly expressed, peristalsis is sluggish, and the gas bubble is enlarged. In infants, there may be an increase in the tone of the stomach muscles in the pyloric region, the maximum manifestation of which is pyloric spasm. Cardiospasm sometimes occurs in older people.

Functional deficiency decreases with age, which is explained, firstly, by the gradual development of conditioned reflexes to food stimuli; secondly, the complication of the child’s diet; thirdly, the development of the cerebral cortex. By two years, the structural and physiological characteristics of the stomach correspond to those of an adult (Bokonbaeva S.D. et al.).

Stomach enzymes

Cells of the gastric mucosa secrete a large number of enzymes. The most important proteolytic enzymes of gastric juice: pepsin, gastrixin (pepsin C), and chymosin (rennin). The pepsin precursor (proenzyme) pepsinogen, as well as the proenzymes gastricsin and chymosin, are produced by the main cells of the gastric mucosa, and are subsequently activated by hydrochloric acid. Non-proteolytic enzymes of gastric juice are lysozyme, carbonic anhydrase, amylase, lipase and others.

Endocrine cells of the stomach

The gastric mucosa contains a large number of endocrine cells that produce a number of hormones.

35% of the endocrine cells of the stomach of a healthy person are enterochromaffin-like cells that secrete histamine, 26% are G-cells that secrete gastrin. In third place in number are D-cells that secrete somatostatin. The figure on the right shows a diagram of the fundic gland (Dubinskaya T.K.):

1 - mucus-bicarbonate layer 2 - surface epithelium 3 - mucous cells of the neck of the glands 4 - parietal cells 5 - endocrine cells 6 - chief (zymogenic) cells 7 - fundic gland 8 - gastric fossa

Microflora of the stomach

Until recently, it was believed that due to the bactericidal effect of gastric juice, microflora that penetrated the stomach died within 30 minutes. However, modern methods of microbiological research have proven that this is not the case. The amount of various mucosal microflora in the stomach of healthy people is 103–104/ml (3 lg CFU/g), including Helicobacter pylori

(5.3 lg CFU/g) detected in 44.4% of cases, 55.5% - streptococci (4 lg CFU/g), 61.1% - staphylococci (3.7 lg CFU/g), 50% - lactobacilli (3.2 lg CFU/g), 22.2% - fungi of the genus

Candida

(3.5 lg CFU/g).

In addition, bacteroides, corynebacteria, micrococci, etc. were sown in an amount of 2.7–3.7 lg CFU/g. It should be noted that Helicobacter pylori

was detected only in association with other bacteria.

The environment in the stomach turned out to be sterile in healthy people only in 10% of cases. Based on their origin, the microflora of the stomach is conventionally divided into oral-respiratory and fecal. In 2005, strains of lactobacilli that adapted (like Helicobacter pylori

) to existing in the sharply acidic environment of the stomach were discovered in the stomach of healthy people:

Lactobacillus gastricus, Lactobacillus antri, Lactobacillus kalixensis, Lactobacillus ultunensis

.

In various diseases (chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, stomach cancer), the number and diversity of bacterial species colonizing the stomach increases significantly. In chronic gastritis, the largest amount of mucosal microflora is found in the antrum, in peptic ulcer disease - in the periulcerous zone (in the inflammatory ridge). Moreover, the dominant position is often occupied not by Helicobacter pylori

, but by streptococci, staphylococci, enterobacteria, micrococci, lactobacilli, and fungi of the genus

Candida

(Y.S. Zimmerman).

According to Engstrand L. (2012), in the stomach of a healthy person, in the absence of dominance of Helicobacter pylory

, the main volume of the gastric microbiota is represented by ten genera:

Prevotella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Rothia, Haemophilus, Actinomyces, Fusobacterium, Neisseria, Porphyromonas

and

Gemella

, belonging to five types (lat.

phylum

) of bacteria:

Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria

and

Fusobacteria

.

Spectrum and frequency of occurrence of microorganisms in the mucous membranes of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum of healthy people (Julai G.S. et al.)

In addition to

Helicobacter pylori,

other representatives of the genus

Helicobacter

.

Patients in whom non-H. pylori Helicobacter species, suffered from gastritis, peptic ulcers, stomach cancer and MALT lymphoma. Although these bacteria are often incorrectly called " Helicobacter heilmannii

", a number of similar but distinct important bacterial species are actually implicated in the development of gastric pathologies, including

Helicobacter bizzozeronii, Helicobacter felis, Helicobacter heilmannii, Helicobacter salomonis

and

Helicobacter suis species.

Diagnosis of infections caused by non-H. pylori Helicobacter pylori agents is not always simple, partly due to their focal colonization in the human stomach (Starostin B.D. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection - Maastricht V / Florence consensus report).

Some diseases and conditions of the stomach

Some stomach diseases and syndromes (see):

- gastritis

Perforation of the stomach - a complication of peptic ulcer - acute gastritis

- chronic gastritis

- atrophic gastritis

- anacid gastritis

- superficial gastritis

- antral gastritis

- reflux gastritis

- Ménétrier's disease

- infectious gastritis*

- Helicobacter pylori

-induced gastritis - bacterial gastritis not associated with Helicobacter pylori

- Helicobacter heilmannii

- associated gastritis - enterococcal gastritis

- anisacidosis of the stomach

- strongyloidiasis of the stomach

- cryptosporidosis of the stomach

| Filippova M.P. Peptic ulcer disease. Lecture for the 2nd year of the FKP MGMSU named after. A.I. Evdokimova (video) |

- postprandial distress syndrome

*Classification of infectious gastritis follows the Kyoto global consensus.

Neoplasms:

- stomach cancer

- stomach polyps and polyp-like formations

- gastric adenomas

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Gastric motility disorders:

- "irritable" stomach

- "lazy" stomach

Some symptoms that may be associated with stomach problems:

- stomach ache

- nausea

- vomit

- gastralgia

Acidity chart for duodenogastric reflux (Storonova O.A., Trukhmanov A.S.)

Patient Materials

- Vasilenko V.V. Stomach // www.gastroscan.ru. 2022.

- Agapkin S.N. The most important thing about the stomach and intestines. Peptic ulcer // Eksmo Publishing House LLC. Moscow. 2022. 53 p.

- Vasilenko V.V. Stomach and resorts / www.gastroscan.ru. 2018

The GastroScan.ru website contains: a subsection “Doctors' Advice” in the “Patients” section of the site, a subsection “Popular Gastroenterology” in the “Literature” section, as well as a subsection “Popular Gastroenterology” in the “Video” section, containing materials for patients on various aspects of gastroenterology.

Publications for healthcare professionals regarding gastric anatomy, physiology and diseases

- Matveeva L.V., Usanova A.A., Mosina L.M. Physiology of the stomach: monograph / Saransk, 2012. – 100 p.

- Butov M.A., Kuznetsov P.S. Examination of patients with diseases of the digestive system. Part 1. Examination of patients with stomach diseases. A textbook on propaedeutics of internal diseases for 3rd year students of the Faculty of Medicine. - Ryazan. — 2007.

- Rapoport S.I., Lakshin A.A., Rakitin B.V., Trifonov M.M. pH-metry of the esophagus and stomach in diseases of the upper digestive tract / Ed. Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences F.I. Komarova. — M.: ID MEDPRACTIKA-M. — 2005. – p. 208.

- Stupin V.A., Siluyanov S.V. Violation of the secretory function of the stomach in peptic ulcer // Russian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Coloproctology. - 1997. - No. 4. - p. 23–28.

- Korotko G.F. Organization of gastric digestion // Bulletin of surgical gastroenterology. - 2006. - No. 1. - p. 17–25.

- Zimmerman Ya.S. Modern methods for studying the functions of the stomach and their diagnostic capabilities // RZHGGK. - 2011. - T.21. - No. 5. — P.4-16.

- Lysikov Yu.A., Goryacheva O.A., Tsvetkova L.N., Krasavin A.V., Gureev A.N., Tsvetkov P.M. Clinical and morphological features of duodenal ulcer in children // Pediatrics. 2011. Volume 90. No. 2. pp. 38–42.

- Levit R.M. Clinical, endoscopic and morphological characteristics of chronic gastroduodenitis in childhood. Abstract of dissertation. Doctor of Medical Sciences, 01/14/08 – pediatrics, YSMU, Moscow, 2016.

- Kolesnikova I.Yu., Volkov V.S. Diagnosis and treatment of acid-related diseases of the digestive tract. Guide for doctors / M.: Publishing House “Medical Information Agency”, 2014. - 432 p.

- Guseinov A.Z., Bronshtein P.G., Sazhin V.P. Stomach surgery monograph // St. Petersburg - Tula: Tula State University Publishing House, 2014. - 264 p.

- Maev I.V., Andreev D.N., Zaborovsky A.V. Fundamentals of acid production in the stomach. Medical advice. 2018;(3):7-14.

On the website GastroScan.ru in the “Literature” section there is a subsection “Diseases of the stomach and duodenum”, containing publications for healthcare professionals. Back to section

Diagnosis of oral leukoplakia

Treatment of any disease begins with diagnosis: leukoplakia is no exception in this regard.

During the examination, the doctor interviews the patient to determine the factors contributing to the development of the disease. These include regular exposure to tobacco smoke, working in hazardous conditions, recent dental surgery, etc.

Next, laboratory tests are prescribed. The following procedures can be carried out:

- tissue sampling (biopsy). Accompanied by anesthesia;

- examination of the collected material under a microscope. The method allows you to determine the presence or absence of cancer cells in the formation;

- a smear of the mucous membrane is taken;

- A Schiller test is done (the mucous membrane is stained with a solution consisting of water and iodine - foci of leukoplakia are not stained);

- blood is taken for analysis (an increase in ESR may indicate the presence of malignant neoplasms).

In addition, the doctor may additionally prescribe a urine test, conduct a biochemical blood test and request the result of fluorography. You may need to consult an oncologist (if cancer is suspected), a therapist (to rule out infectious diseases) and a dermatologist (to look for other foci of disease).

Leukoplakia of the oral cavity: treatment with medications

Treatment involves the complete elimination of irritating factors that led to the development of the disease:

- to give up smoking;

- grinding down sharp edges of teeth;

- sanitation of the oral cavity;

- replacement of fillings;

- use of products to protect the surface of the lips.

Additionally, a course of vitamin A is prescribed, lasting at least a month, which inhibits the process of tissue keratinization.

If the measures taken do not cause complete disappearance of the manifestations of the disease, surgical intervention is allowed: the lesion is excised, depending on the degree of development of the disease, cryodestruction or electrocoagulation is used.

Ulcers deserve special attention, as they can develop into cancerous tumors. For their treatment, drugs are prescribed that enhance the process of tissue regeneration and epithelization. If there is no positive dynamics, surgical intervention cannot be avoided.

A person with leukoplakia must constantly visit the dentist for examination to prevent malignant degeneration of the cells.

In addition to quitting smoking, the patient’s diet is adjusted: during treatment, spicy and too salty foods are excluded from the diet, and it is recommended to eat more vegetables and fruits.

Drugs prescribed:

- products that restore the epithelium (the most effective was 30 percent tocopherol acetate, which is applied to damaged areas three times a day for 15 minutes, after which it is washed off with water);

- antiseptics (after each meal it is recommended to rinse your mouth with a solution of chlorhexidine at a concentration of 0.05%);

- analgesics (their use is justified in the presence of pain. Lidocaine, applied to the mucous membrane before meals, has worked well).

Under no circumstances should you use drugs that have an irritating effect, as otherwise this can lead to the formation of cancer cells.

If there is no improvement within a couple of weeks, surgery is prescribed: this can be either excision with a scalpel or the application of cold in the form of a liquid stream of nitrogen.

Chemical injuries to the oral mucosa in children.

These injuries are observed mainly in children 1–3 years old due to accidental ingestion of solutions of acids and alkalis used in everyday life. In this case, combined burns of the mucous membrane of the mouth, pharynx, and esophagus develop. The severity of the lesion is determined by the concentration of the drug and the duration of its effect. The mucous membrane becomes sharply hyperemic, then necrosis appears within a period of several hours to a day, the deepest usually on the lower lip. Necrotic tissues become saturated with fibrinous exudate; a thick film is formed, which is slowly torn off on the 7th - 8th day and at a later date. In an uncomplicated course, under such a film, tissue scarring and epithelization of the defect occur in parallel.

Chemical burns can be caused by many medications used in dental treatment: phenol, formalin, antiformin, acids, alcohol, ether, etc., so the dentist should be especially careful when using them, taking into account the easy vulnerability of the mucous membrane in children and the often violent reaction of the body in response to its damage.

TREATMENT OF CHEMICAL INJURIES OF THE ORAL MUCOSA IN CHILDREN.

For chemical burns in the first minutes and hours, it should be aimed at neutralizing the chemical agent with 1 - 2% solutions of sodium bicarbonate for acid burns and 1% hydrochloric acid solution or 3% citric acid solution for alkali burns. Further treatment consists of preventing secondary infection of the lesion and pain relief. For burns of the pharynx and esophagus, the child should be hospitalized in the ENT department.

Oral leukoplakia: how to treat it at home

In addition to drug treatment, oral leukoplakia can be treated with traditional medicine.

There are many recipes, here are just the main ones:

- rinsing with herbs (infusions of oregano, chamomile, ginseng and other adaptogens that reduce the inflammatory process and increase the body’s resistance to harmful factors are suitable);

- regular consumption of nuts and tinctures based on them;

- rinsing with decoctions of calendula, St. John's wort, eucalyptus. Alternation works well - once the oral cavity is rinsed with a soda solution, after a couple of hours - with an infusion of herbs. This procedure should be repeated at least 5 times a day;

- lubricating the lesions with sea buckthorn and olives (the fruits must first be mashed in your hands so that the juice appears).

Timely detection of the disease and compliance with all doctor’s recommendations is the key to recovery in the shortest possible time and reducing the risk of complications. If you start treatment at the initial stage, you can reduce the likelihood of complications to almost zero.