Trigeminal and facial neuralgia

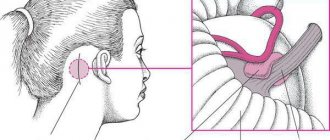

Neuralgia is a disease in which damage or compression of the trigeminal nerve and/or its branches occurs. This causes a sharp piercing pain that occurs suddenly and brings physical and psychological discomfort to the patient. Despite the fact that the term “neuralgia” can be literally translated as “nerve pain,” the matter is not limited to pain. Trigeminal and facial neuralgia are radically different in symptoms. The facial nerve contains mostly motor fibers, so neuralgia leads to dysfunction of the facial muscles (the degree depends on the severity of the disease), and can also cause lacrimation, dry eyes and partial loss of taste. Pain in facial neuralgia is usually concentrated in the area of the parotid gland (the patient complains that the pain radiates to the ear), but there may be no pain at all. It is because of the lack of pain that some experts use the term “neuropathy” when talking about damage to the facial nerve. With the trigeminal nerve it’s exactly the opposite, since it contains many sensory fibers.

Complications

For fear of provoking a painful attack, patients begin to chew with one part of their mouth, which causes the formation of compactions in the muscles of the healthy half of the face.

Frequent attacks significantly worsen the quality of life of patients, which affects changes in their psycho-emotional state and performance.

Prolonged and severe pain, being in constant fear of the onset of another attack provoke the development of neurotic and mental disorders (neurosis, depression, hypochondria).

In the case of progressive demyelination and degenerative processes, the trigeminal nerve begins to function worse and worse, the sensitivity and motor activity of the facial and chewing muscles decreases, which leads to its atrophy.

Symptoms of neuralgia

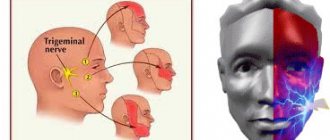

- Facial pain (prosopalgia). A characteristic sign of neuralgia. Sharp and sudden, reminiscent of an electric shock. Usually lasts from 5 to 15 seconds, is paroxysmal in nature and can occur at any time. During periods of remission, the number of attacks decreases. Most often, pain occurs in the area of the cheekbones and lower jaw (both right and left), and can be localized in almost all areas of the face.

- Impaired sensitivity. A severe form of neuralgia can lead to partial or complete loss of sensitivity of the skin.

- Nervous tic of the eyelid (nystagmus), spasms and twitching of facial muscles.

- Loss of coordination and motor skills are rarer manifestations of severe forms of the disease.

- Headaches, fever, chills and weakness are syndromes caused by viruses and infections.

Causes

Unlike neuritis, neuralgia is not an inflammatory disease. Fever, fever, swelling and other symptoms of the inflammatory process are not associated with this disease. However, if the trigeminal nerve is damaged due to neuritis, pain sensations that fit the description of neuralgia may well occur. To avoid confusion and differentiate the two pathologies, it is necessary to consider their etiology.

The cause of neuritis (like any other inflammatory disease) is viruses and infections that cause gradual destruction of the membrane and nerve trunk, and classical neuralgia in the vast majority of cases occurs due to mechanical effects on the nerve. Today, experts identify dozens of factors that provoke the development of the disease.

Main causes of neuralgia

- Head injuries leading to changes in the cranial structure and displacement of bones.

- Benign and malignant tumors that, as they grow, compress the trigeminal nerve.

- Various bite pathologies and other dental anomalies.

- Pathologies of the structure and diseases of blood vessels located in close proximity to the nerve (atherosclerosis, aneurysm, vasodilatation, etc.).

- Sinusitis and otitis in chronic form.

- Trigeminal neuralgia after tooth extraction. Occurs during a traumatic or incorrectly performed extraction procedure.

- Damage as a result of infection resulting from a number of diseases: periodontitis, periodontitis, stomatitis, herpes, syphilis.

Trigeminal neuralgia from hypothermia occurs rarely. However, this factor contributes to the development of the disease and complicates treatment. The same can be said about decreased immunity, metabolic disorders, neurosis, diabetes and other complicating factors.

Introduction

Often today, doctors, both neurologists and dentists, attribute all prosopalgia to trigeminal neuralgia.

Anticonvulsants, alcoholization of the peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve, and analgesics are widely used in treatment. This does not take into account that pain in the facial area can be caused by other neurodental diseases, the treatment of which with similar methods does not bring relief and only worsens the picture [1–3]. In case of orofacial pain, in 83% of cases there is an overdiagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia and in 100% of cases there is an underdiagnosis of atypical facial pain. Incorrect diagnosis leads to unnecessary surgical interventions: in 24% of patients, a tooth or even several are removed [4]. The term “atypical facial pain” was first coined in 1924 by Fraizer and Russell to refer to patients with prosopalgia for whom neurosurgical treatment had failed.

In 1999, A. Woda and P. Pionchon introduced the concept of chronic idiopathic facial pain, including in this group of prosopalgia atypical facial pain and pain dysfunction syndrome of the temporomandibular joint [5].

In the International Classification of Headache Disorders II Revision (ICHD-II) of 2004, persistent idiopathic facial pain is classified under the section “Central facial pain” [6]. Previously, the term “atypical facial pain” was used to designate persistent idiopathic facial pain that did not meet the diagnostic criteria for cranial neuralgia and was not associated with other pathology. According to epidemiological data, the prevalence of atypical pain among patients with chronic orofacial pain is about 5–10%. In a large epidemiological study of 34,242 dental patients, chronic facial pain was reported in 5.2% of patients. Among patients with chronic facial pain, atypical facial pain occurred in 5.8% of cases [7].

Risk factors for the development of atypical facial pain include genetic predisposition, female gender, and passive coping strategy [8]. The study showed that the level of estrogen in the blood of patients with atypical facial pain is increased. The formation of cavities in the bone tissue of the jaws during menopause in women is also considered a factor contributing to the development of atypical prosopalgia. One of the factors that determines the maladjustment of patients with atypical facial pain includes emotional and personal disorders, which are often difficult to recognize. This is due both to the polymorphism of such disorders and to the fact that other manifestations of the disease can mask them.

Patients describe their sensations in great detail. One of the characteristic features of atypical facial pain is that during repeated surveys, the patients’ complaints often do not coincide with those during previous surveys. Patients are characterized by egocentrism, they are characterized by capriciousness, painfully heightened imagination, and a tendency to exaggerate their painful disorders. Increased excitability is combined with irritability, fatigue, decreased performance, and sleep disorders. Low quality of life, high levels of depression and anxiety, the predominance of excitable and unbalanced types of character accentuations adversely affect the effectiveness of treatment [9].

The distribution of areas of sensory impairment is extremely diverse, but, as a rule, they do not correspond to the innervation of the cranial nerves. Often this is hypoesthesia, less often hyperesthesia with a regular geometric shape and clearly defined boundaries. However, if the patient is familiar with sensory disturbances in the face or oral cavity due to neurodental diseases, he can simulate the area of anesthesia corresponding to that which occurs with these diseases. Sensitivity disorders turn out to be quite persistent. They can disappear as suddenly as they appear.

It is always quite difficult to distinguish atypical facial pain from typical neuralgia. In this case, a pharmacological test can help: prescribing carbamazepine for suspected trigeminal neuralgia or analgesics for suspected neuropathy. The patient should not know about the nature of the drug’s action and the true purpose of the test. The absence of an analgesic effect of carbamazepine or an analgesic indicates rather an atypical nature of the pain.

Diagnostic criteria for atypical facial pain [4,10]:

- Daily facial pain for most of the day, meeting criteria 2 and 3.

- The pain is initially localized in the nasolabial fold or chin, limited to a certain area of one half of the face, then can spread to the upper and lower jaws, other areas of the face and neck; dull pain of uncertain localization.

- Sensory disturbances and other neurological symptoms are absent.

- Instrumental studies, including x-rays of the facial skull and jaws, do not reveal organic changes.

Pain can be triggered by facial surgery, trauma to the face, teeth or gums, but its persistence cannot be attributed to a local cause. Atypical facial pain serves as a diagnosis of exclusion.

The diagnostic algorithm for atypical odontogenic pain includes [11]:

- analysis of patient complaints and the nature of facial pain;

- studying the medical history: the time of occurrence of facial pain, its possible connection with various diseases or a traumatic situation;

- identifying areas of maximum pain intensity, i.e. areas of initial occurrence and dominance of pain;

- study of the somatic and neurological status of the patient;

- conducting neuropsychological studies;

- additional research necessary for each specific case: consultation with a dentist, therapist, neuro-ophthalmologist, ENT doctor, neurosurgeon; examination of cerebral vessels, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, general blood and urine analysis, biochemical blood test;

- evaluation of research results.

The group of odontogenic atypical pain includes odontogenic atypical neuralgia, dental plexalgia, and osteonecrosis inducing neuralgia (NICO syndrome).

Odontogenic atypical neuralgia

The history of odontogenic atypical neuralgia begins in 1947 and is associated with the names of TW McElin and BT Horton [12]. In the domestic literature, the first description of this disease belongs to V.E. Grechko and M.N. Puzin (1979). In their opinion, odontogenic neuralgia is characterized by a clear connection between the pain syndrome and the pathology of the dental system. A typical sign is that pain paroxysms last for hours or days and subside gradually. The picture of pain can vary and to a certain extent depends on the process in the dental system. The therapeutic effect occurs from taking analgesics with reflexology. Prescription of carbamazepine drugs gives a slight reduction in pain or is ineffective. Alcohol-vocaine blockades are also ineffective [13].

In the work of D. Nixdorf et al. (2010) reviewed prospective studies on the occurrence of atypical facial pain after dental procedures. The incidence of this complication is believed to be 3.4% [14]. The most common cause leading to the occurrence of odontogenic atypical neuralgia is complicated removal of teeth and remnants of their roots; Then there are defects in fillings and prosthetics, inflammatory and traumatic processes in the dentoalveolar region, and the simultaneous removal of three or more teeth in preparation for prosthetics. After complex medical manipulations in the oral cavity associated with the removal of teeth and remaining roots, patients experience persistent pain in the area corresponding to the branch of the trigeminal nerve after a few days. It is characteristic that pain, which at the onset of the disease is localized in the socket of the extracted tooth, subsequently diffusely spreads to the corresponding half of the jaw and the area of innervation of the trigeminal nerve branch [15].

The pathogenesis of atypical facial pain is not completely known. This form of facial pain is classified as chronic prosopalgia. Peripheral and central sensitization, weakening of the activity of descending antinociceptive noradrenergic and serotonergic systems of the brain are discussed as possible causes. Hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system, caused by stress, leads to disruption of the interaction of the monoaminergic, neuropeptide and glutamatergic systems. It is assumed that during dental treatment, damage to the nerve fibers at the apex of the tooth root occurs, which is regarded as traumatic neuralgia. Another possible cause is the formation of a small traumatic neuroma in the apical periodontium [16, 17]. The onset of pain is associated with an increase in the flow of nociceptive signals, a decrease in the threshold of excitability of afferent fibers, the formation of loci of spontaneous ectopic activity in damaged nerves, and hyperexcitability of nociceptive neurons of the spinal cord and brain.

Psychological factors are also involved in the development of odontogenic atypical trigeminal neuralgia. RT Rees and M. Harris (1978–1979), examining 44 patients with odontogenic atypical neuralgia, found depression in 66% of cases. The mood of patients is usually low, they are fixated on their painful sensations, and are conflicted [18]. RI Brooke and RF Schnurr (1995) among 22 patients with odontogenic atypical neuralgia observed depression in 41% of cases. Odontogenic atypical trigeminal neuralgia occurs more often in women than in men (2:1). The highest frequency occurs between the ages of 40–69 years. The third branch of the trigeminal nerve is most often involved, less often the second, and neuralgia of the second and third branches is very rare [19].

The main factors in the chronic course of atypical facial pain include personality traits, prolonged emotional stress, abuse of analgesics and depressive disorders. All four factors can be present simultaneously.

Odontogenic atypical neuralgia often has an acute onset, paroxysmal or chronically recurrent course. Against the background of constant pain, there are attacks of increased pain, lasting from 20 minutes to several hours, less often – days. Provoking factors can be stressful situations, physical activity, climate change.

Difficulties in diagnosing atypical odontogenic pain are associated with the diversity of its clinical manifestations and localization, variability in the nature and “pattern” of pain. According to the 3rd edition of the International Classification of Headache Pain (ICHD, 2013), odontogenic atypical trigeminal neuralgia belongs to paragraph 13.18 - persistent idiopathic facial pain (PIFP). Odontogenic atypical neuralgia is a type of PILB, in which pain is localized in the area of the teeth or dental socket in the absence of clinical and radiological signs of dental and periodontal pathology [20, 21].

The following diagnostic criteria are characteristic of odontogenic atypical trigeminal neuralgia: 1) constant dull, aching, throbbing pain of varying intensity in the teeth of the upper and lower jaws, which can periodically worsen; 2) pain is often limited to the area of innervation of individual nerves within the main branches of the trigeminal nerve (usually II and III) or branches of the dental plexuses; 3) periods of exacerbation of pain last for hours and subside gradually; 4) there are no trigger areas; 5) the causes of local or referred pain are not identified, there are no clinical or radiological signs of the pathological process; 6) local irritation (hypothermia of the face, eating hot or cold food, percussion of teeth) does not cause increased pain; 7) there are no motor disorders caused by neuropathy of the facial or motor part of the trigeminal nerves; long-term course (4 months or more); 9) in some patients, pain intensifies under the influence of emotions, physical activity, and adverse meteorological factors; 10) the reaction to local anesthesia is weak; 11) attempts at dental treatment (tooth extraction) do not produce results; 12) the appearance of pain is usually preceded by surgical interventions (tooth root canal treatment, tooth extraction); hypothermia and trauma can also be provoking factors; 13) the therapeutic effect of taking analgesics [13, 15].

2) pain is often limited to the area of innervation of individual nerves within the main branches of the trigeminal nerve (usually II and III) or branches of the dental plexuses; 3) periods of exacerbation of pain last for hours and subside gradually; 4) there are no trigger areas; 5) the causes of local or referred pain are not identified, there are no clinical or radiological signs of the pathological process; 6) local irritation (hypothermia of the face, eating hot or cold food, percussion of teeth) does not cause increased pain; 7) there are no motor disorders caused by neuropathy of the facial or motor part of the trigeminal nerves; long-term course (4 months or more); 9) in some patients, pain intensifies under the influence of emotions, physical activity, and adverse meteorological factors; 10) the reaction to local anesthesia is weak; 11) attempts at dental treatment (tooth extraction) do not produce results; 12) the appearance of pain is usually preceded by surgical interventions (tooth root canal treatment, tooth extraction); hypothermia and trauma can also be provoking factors; 13) the therapeutic effect of taking analgesics [13, 15].

When assessing the neurological status, 60–70% of patients may experience dysesthesia, paresthesia, and a subjective feeling of numbness, but there are no objective sensory disturbances or other neurological symptoms. In most cases, the pain intensity is moderate (about 7 points on the visual analogue scale). Half of the patients note the presence of chronic fatigue. Affective disorders are detected in 16% of patients, somatoform disorders – in 15%, psychosis – in 6%, other diseases – in 16% [15].

Odontogenic dental plexalgia

In 1973 V.E. Grechko first proposed the term “odontogenic dental plexalgia.” Odontogenic dental plexalgia mainly occurs in women in a ratio of 9:1. The age of patients varies from 30 to 70 years. The duration of the disease varies [13]. The etiological factors for the occurrence of odontogenic dental plexalgia are considered to be defects in filling teeth and root canals, alveolitis, surgical intervention on the jaw, simultaneous removal of three or more teeth in preparation for prosthetics, traumatic (complicated) removal of a wisdom tooth and the remains of its roots. The most common cause of odontogenic dental plexalgia is defects in filling teeth and root canals associated with excessive introduction of filling material into the lumen of the root canal. Trauma to nerve fibers is one of the causative factors of odontogenic dental plexalgia [22]. Pain from trauma to the upper and lower dental plexuses is localized either in the area of the gums and teeth and is usually permanent, or in areas of extracted teeth (in the area of the projection of the upper and lower plexuses). Periodically, it intensifies with a painful attack lasting up to several hours. The nature of the pain is mainly dull and aching. In some patients, pain paroxysm is accompanied by irradiation of pain to the frontal and zygomatic areas. In some patients, pain decreases while eating non-rough food and increases under the influence of emotions, adverse meteorological factors and hypothermia. Some patients indicate that the pain stops at night, while others indicate that it intensifies. The reduction in pain during eating in patients with odontogenic plexalgia is apparently associated with the emergence of a stronger food dominant, which stops the pain dominant. When palpating the exit points of the II and III branches of the trigeminal nerve, some patients experience pain. These are usually patients who have undergone local surgical interventions in the dental system. As a rule, palpation of the exit points of the II and III branches of the trigeminal nerve in dental plexalgia is painless. Sensory disorders are not typical for patients with odontogenic plexalgia. Most patients experience vegetative disorders in the form of swelling of the gums and skin of the buccal area, their hyperemia, which probably occurs as a result of the reflex involvement of vegetative formations in the pathological process, in particular the pterygopalatine and superior cervical sympathetic nodes.

Diagnostic criteria: constant local pain in the gums and teeth, accompanied by attacks of intensification lasting up to several hours; the pain is dull or aching in nature; the upper dental plexus is involved more often than the lower; Dental plexalgia can also be bilateral.

Osteonecrosis inducing neuralgia (NICO syndrome)

The most characteristic signs of NICO syndrome: constant, deep odontogenic pain; a sour or bitter taste that causes bad breath; long-term treatment at the dentist (canal filling, tooth extraction); complicated removal of wisdom teeth; poorly made dentures. A decrease in blood flow in small vessels in the area of wisdom teeth can cause the development of osteonecrosis and the formation of microcavities in the jaws. MRI in STIR mode makes it possible to identify a sparse area of bone with impaired blood supply [23, 24].

The most difficult task is the differential diagnosis between odontogenic atypical neuralgia and inflammatory disease of the dental pulp - pulpitis and myo-orofacial pain syndrome.

Pulpitis

Pain with pulpitis is similar in nature to algic syndrome in odontogenic atypical trigeminal neuralgia due to its irradiation along the branches of the trigeminal nerve. Often in the initial stage of odontogenic atypical trigeminal neuralgia, the pain is localized in one or several teeth, which forces the patient to turn first to the dentist. Pain in a tooth is mistakenly regarded as pulpitis, which leads to unreasonable removal of the pulp. Usually, the pain does not decrease after this, but sometimes intensifies, which entails the removal of one, and often several teeth. Some patients, due to intractable pain, needlessly remove from 3–4 to 7–8 teeth on the affected side. In addition, dental measures do not bring relief to these patients; tooth extraction leads to disruption of the functional state of the dental system, which in turn worsens the course of odontogenic atypical trigeminal neuralgia.

Features of the clinical manifestations of odontogenic atypical neuralgia include constant pain in the tooth in the absence of local pathology; local irritation of the tooth does not cause pain; the intensity of toothache does not change over weeks or months; repeated dental intervention does not eliminate pain; the response to local anesthesia is ambiguous [4, 15, 25].

Myo-orofacial pain syndrome

In 1934, the American otorhinolaryngologist Kosten identified a group of symptoms that arise from malocclusion: headache, clicking in the temporomandibular joint, burning sensation in the tongue and larynx.

However, the main symptom is orofacial pain. For the normal functioning of the dental system, the preservation of the temporomandibular joint, teeth, periodontium and associated muscles is necessary. The interaction of these four parts of the dental system is carried out under the control of the cerebral cortex and subcortical structures. This pain syndrome is characterized by vaguely defined boundaries that do not fit into the area of innervation of the branches of the trigeminal nerve. It may be accompanied by local muscle tension (clicking in the temporomandibular joint). A slight deviation of the lower jaw is often detected. With pronounced emotional stress, a sharp increase in the tone of the chewing muscles and tongue muscles occurs. This increases the discrepancy between the rows of teeth in the upper and lower jaws. The increase in pain in old age may be associated with changes in the facial skeleton. The most important of these are tooth loss and changes in the temporomandibular joints. A relationship was revealed between headache and facial pain and temporomandibular arthropathy.

Diagnostic criteria: decreased occlusal height of the lower face; sharp pain on palpation of the temporomandibular joint; pain when moving the lower jaw; crunching and clicking in the temporomandibular joint; frequent hearing loss; radiographically detectable violations of the integrity of the cortical plate of the articular head, its flattening.

Treatment of atypical odontogenic pain

Once atypical odontogenic pain is diagnosed, dental treatments that may worsen the pain should be avoided.

Carbamazepine and phenytoin are ineffective. Surgical manipulation of the trigeminal nerve is not indicated because it does not relieve pain but may cause painful anesthesia. The basis of treatment for atypical facial pain is antidepressants, primarily tricyclics in the form of monotherapy or in combination with phenothiazine derivatives. It is recommended to start treatment with small doses of amitriptyline (25 mg/day) and slowly titrate the dose until the effect is achieved (up to 150 mg/day) [22].

It should be noted that in most cases, the effect of low doses of antidepressants develops gradually - over 1-2 weeks. This should be kept in mind and not interrupt therapy if it does not have an effect in the first days. If there is no effect within 1–2 weeks, it is possible to increase the dose of the drug or switch to another drug. When the desired effect is achieved, daily doses of the drug are reduced gradually: a sharp reduction in doses or discontinuation of the drug can provoke withdrawal syndrome, deterioration of both mental and somatic conditions. In most cases (taking into account the severity and duration of the disease), long-term (up to 6 months or more) use of antidepressants in maintenance doses is indicated. The use of tricyclic antidepressants is limited by their side effects: increased intraocular pressure, dry mouth, weight gain, constipation and urinary retention. They are contraindicated in patients with angle-closure glaucoma, intraocular hypertension, as well as in those taking MAO inhibitors, barbiturates, anticholinergic drugs and sympathomimetics. The use of phenothiazine derivatives is limited by the development of neuroleptic syndrome.

There is currently no information on the optimal timing and duration of antidepressant therapy. Preference is given to early initiation of therapy and their long-term use. Thus, a number of studies have shown that patients who began treatment with antidepressants in the first month from the onset of the disease subsequently demonstrated better functional recovery than those who did not receive treatment and those for whom it began at a later date.

In some cases, the effectiveness of gabapentin, clonazepam, baclofen, doxepin, aspirin, phentolamine, and MAO inhibitors has been reported [26]. It is possible to treat odontogenic atypical trigeminal neuralgia by applying local capsaicin cream to the area of pain for four weeks.

A necessary addition to drug treatment is the administration of drugs with a predominantly antiasthenic effect, such as B vitamins, preferably in the most bioavailable form.

It is known that vitamin B1 (thiamine) regulates protein and carbohydrate metabolism in the cell and affects the conduction of nerve impulses. Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) is a cofactor for many enzymes, participates in the synthesis of neurotransmitters, and supports the synthesis of transport proteins. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is part of enzyme systems that catalyze the synthesis of nucleotides and nucleic acids.

Experimental studies have described the antinociceptive effect of B vitamins (B1, B6, B12). It is believed that their point of application is participation in serotonin metabolism: pyridoxine is involved in the synthesis of serotonin as a coenzyme, thiamine is involved in its deposition and transport [27].

Treatment also includes eliminating a conflict situation, individual or group cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, removing the patient from the environment that provoked the disease, relaxation methods aimed at distracting the patient from the sensation of pain, and developing an adaptive strategy for overcoming pain. Rational rest is necessary. Autogenic training can be recommended.

Classification of the disease

Due to the occurrence

- Primary (idiopathic) trigeminal neuralgia. A classic type of neuralgia, so to speak. Occurs due to compression of the trigeminal nerve.

- Secondary trigeminal neuralgia is a consequence of other diseases and viruses.

By coverage

- Unilateral (one branch of the trigeminal nerve is affected).

- Bilateral (more than one branch is affected).

Neuralgia can affect the 1st, 2nd, 3rd branches of the trigeminal nerve. The first branch is responsible for the orbital zone, the second for the median zone (including the nose and upper lip), and the third for the lower jaw. Most often, damage to the third branch is diagnosed, so the pain affects the area of the lower jaw, and an attack often occurs during hygiene, eating or shaving.

Types of trigeminal neuralgia

There is an additional classification that can also be used in making a diagnosis.

Acute

Acute trigeminal neuralgia, accompanied by frequent and severe attacks.

Chronic

Chronic trigeminal neuralgia is a consequence of an untreated disease. The patient has been observed for a long time: remissions alternate with exacerbations.

Atypical

Atypical trigeminal neuralgia occurs against a background of stress and nervous exhaustion (psychosomatics).

Postherpetic

Postherpetic trigeminal neuralgia occurs after a history of herpes and its symptoms differ from the classic type. The pain is usually burning and may not go away for two to three hours.

Therapeutic methods

If tooth pulpitis is diagnosed, treatment can be carried out in two ways:

- surgical – tooth depulpation is performed;

- conservative - it is possible to preserve the pulp.

Surgery

This method is traditional and is used in most cases. But in this case, the tooth after pulpitis changes its color and becomes more fragile.

Depulpation (the so-called procedure for removing a nerve) can be performed either after preliminary killing of the nerve or without it.

Surgical treatment is carried out in several stages:

- an anesthetic is administered;

- remove the pulp and eliminate tissue damaged by caries;

- estimate the length of the channels;

- install a temporary filling;

- if no complications arise, then at the second visit they clean, expand, wash with antiseptic agents and seal the canals, having previously installed the pins;

- install a permanent filling on the dental crown.

The quality of the filling is controlled using x-rays.

Conservative treatment

Preserving the pulp is only possible in children and people under 30 years of age if they went to the dentist at the initial stage of the disease, which happens extremely rarely, since most people endure pain until the last moment. If purulent processes begin in the pulp, it will have to be removed.

The conservative method involves thorough treatment of the dental cavity with medications, after which a filling is installed.

Diagnosis of the disease

Modern medicine has in its arsenal many diagnostic techniques that make it possible to determine the type of neuralgia and the cause of its occurrence:

- visual examination and questioning of the patient;

- X-ray of the jaw;

- MRI of the brain and blood vessels;

- laboratory analysis of urine and blood;

- electromyography.

Diagnosis is carried out by a neurologist, but additional examinations by other specialists are often required: dentist, ophthalmologist, otolaryngologist. Particular attention is paid to differential diagnosis, since neuralgia may resemble other diseases in its symptoms, in particular glaucoma, otitis media, ethmoiditis, Slader syndrome, etc.

Our doctors

Pankov Alexander Rostislavovich

Neurologist

41 years of experience

Make an appointment

Novikova Larisa Vaganovna

Neuropathologist, Candidate of Medical Sciences, doctor of the highest category

40 years of experience

Make an appointment

Belikov Alexander Valerievich

Neurologist, Candidate of Medical Sciences

22 years of experience

Make an appointment

Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia

Treatment and drugs

For successful treatment, complex drug therapy is used. First of all, these are anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, finlepsin or clonazepam), which are included in the mandatory rehabilitation program and relieve the main manifestations of neuralgia. The dosage and duration of treatment are determined strictly by the attending physician.

For additional effect, antihistamines and local pain relievers may be prescribed. To compensate for the lack of gamma-aminobutyric acid (a kind of mediator between the brain and the nervous system), baclofen, phenibut or gabapentin are prescribed. In the stage of exacerbation of neuralgia, specialists often prescribe antidepressants to eliminate psychological discomfort (the most common remedy is finlepsin). If the cause of the disease is a virus or infection, antiviral and antibacterial agents, as well as NSAIDs, are prescribed. During the recovery period, it is recommended to take B vitamins.

Physiotherapy

To eliminate pain, novocaine blockades and sodium hydroxybutyrate injections are actively used. The most popular and effective physiotherapeutic techniques: acupuncture, ultraphonophoresis, magnetic therapy, and low-frequency laser therapy. Massage for trigeminal neuralgia is also a good addition to general treatment and allows for better blood circulation.

Help at home

Acute toothache requires immediate contact with a dental clinic. And home treatments are in no way a substitute for visiting a doctor. They should be used only if the patient is outside the city and there are no medical facilities nearby. Or at night, when you need to wait several hours before seeing a doctor.

First of all, the patient should be offered anti-inflammatory drugs. They also have analgesic and antipyretic effects. Among them are Solpadeine, Nimesulide, Paracetamol, Ibuprofen and their analogues.

Traditional methods of treatment include rinsing with soda solution or chamomile infusion. They have an anti-inflammatory and antiseptic effect and will help slightly relieve pain.

It is worth remembering that these methods have a temporary effect. They are not curative and do not eliminate the cause of the disease. Therefore, you should not delay contacting a specialist. This will help avoid serious complications and tooth loss.