What are furcation lesions?

Furcation damage is the process of loss of bone tissue in the area of branching of the roots of the tooth. Typically, bone loss is a consequence of periodontal disease. Periodontium is a complex of tissues that surround and hold the tooth in the bone.

Almost all periodontal diseases are caused by the accumulation of plaque (plaque). Thus, high-quality and regular removal of plaque and stones is a mandatory, integral part of the course of treatment of periodontal diseases. As periodontal disease progresses, plaque and tartar begin to form on the root surface. In this case, the patient will no longer be able to independently remove microbial contamination. When the lesion reaches the furcation, self-cleaning becomes impossible.

Assessing furcation involvement The first step is to determine the presence and extent of furcation involvement. For this purpose, special (periodontal) curved probes are used, which are inserted by the doctor into the furcation area. The second step is to conduct an x-ray examination, which will help to visualize the existing defect.

Classification of furcations depending on the severity of the lesion

Normal state of tooth furcation

Class 1 (initial changes) - on an x-ray, the affected area can be visualized as a groove

Class 2 (moderate damage) – the depth of the bone defect is 1-2 mm

Grade 3 - significant bone loss in the furcation area

Treatment Treatment of furcation lesions is a complex and painstaking task for both the doctor and the patient. Cleansing the furcation area is usually carried out using special scalers and currets. Drug therapy consists of taking or topical application of antimicrobial and antibacterial drugs. There are also surgical techniques for the treatment of furcation defects, which have two main goals: to make the furcation area more accessible for cleansing or to regenerate lost bone and soft tissue. The possibility of regeneration largely depends on the severity of the lesion; with significant defects, this procedure may not give positive results.

Prognosis The future of teeth with furcation defects of bone tissue is largely determined by how well the patient maintains oral hygiene and how regularly he visits the hygienist.

based on materials from the site www.deardoctor.com

Furcation defects - diagnostic basics

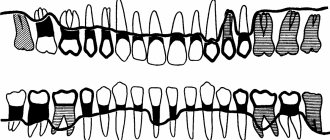

Molars of the upper jaw As a rule, the first molar of the upper jaw is in all respects - crown and individual roots - larger than the second molar, which in turn is larger than the third molar. The first and second molars most often have three roots: one mesiobuccal, one distobuccal, and one palatal. The mesiobuccal root is usually vertical, while the distobuccal and palatal roots are inclined. The distobuccal root projects distally, and the palatal root projects in the palatal direction (Figure below). The cross-sections of the distobuccal and palatal roots are usually circular. The palatal root is generally wider in the mesio-distal than in the bucco-palatal direction. The distal surface of the mesiobuccal root has a concavity that is about 0.3 mm in depth (Bower 1979a, b). This concavity gives the cross-section of the mesiobuccal root an “hourglass” configuration (Figure below). The three furcation entrances of the maxillary first and second molars vary in width and are located at different distances apical to the CEJ. Typically, the first molar has a shorter root shaft than the second molar. In the first molar, the mesial furcation entrance is located approximately 3 mm from the CEJ, while the buccal entrance is 3.5 mm and the distal entrance is approximately 5 mm apical to the CEJ (Abrams & Trachtenberg 1974; Rosenberg 1988). This means that the furcation vault is inclined; in the mesiodistal plane, the arch is relatively close to the CEJ on the mesial surface, but closer to the apex on the distal surface. The buccal furcation entrance is narrower than its distal and mesial counterparts. The degree of root separation and divergence decreases from the first to the second and from the second to the third maxillary molar. The mesiobuccal root of the first molar is often positioned more buccally in the arch than the distobuccal root. If the buccal bone plate is thin, the mesial buccal root often protrudes through the outer surface of the alveolar bone and bony fenestrations and/or dehiscence may occur. Maxillary premolars In approximately 40% of cases, maxillary first premolars have two roots, one buccal and one palatal, and therefore have a mesiodistal furcation. A concavity (about 0.5 mm in depth) is often present in the buccal root furcation. In many cases, the furcation is located in the middle or apical third of the root complex (Figure below). The average distance between the CEJ and the furcation entrance is approximately 8 mm. The width of the furcation entrance is about 0.7 mm. Molars of the mandible The first molar of the mandible is larger than the second molar, which in turn is larger than the third molar. In first and second molars, the root complex almost always includes two roots, one mesial and one distal. The mesial root is larger than the distal root. The mesial root has a predominantly vertical position, while the distal root projects distally. The mesial root is wider buccolingually and has a larger cross-sectional area than the distal root. The cross-section of the distal root is circular, while the mesial root is hourglass shaped. In addition, grooves and concavities are often found on the distal surface of the mesial root (Fig. below). The distal concavity of the mesial root is more pronounced than that of the distal root (Bower 1979a, b; Svärdström & Wennström 1988). The root shaft of the first molar is often shorter than the shaft of the second molar. The furcation entrances of the mandibular first molar, similar to those of the maxillary first molar, are located at different distances from the CEJ. Thus, the lingual inlet is often found more apical to the CEJ (>4 mm) than the buccal inlet (>3 mm). Thus, the furcation vault is inclined in the buccolingual direction. The buccal furcation inlet is often <0.75 mm wide, while the lingual inlet is generally >0.75 mm wide (Bower 1979a, b). The degree of separation and divergence between the roots decreases from the first to the third molar (Fig. below). It should also be noted that the buccal bone plate is thinner outside the roots of the first than of the second molar. Fenestration and dehiscence of bone tissue, as a result, are more common in the area of the first molar than in the area of the second. Other Teeth Furcations may also be present in teeth that usually have only one root. In fact, there may be double-rooted incisors (picture below), canines (picture below) and mandibular premolars. Sometimes there are three-rooted maxillary premolars (Fig. below) and three-rooted mandibular molars (Fig. below).

Root trunk length[edit]

The distance between the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) and the entrance to the fork is called the root length

. This distance plays an important role in furcation defects because the deeper the entrance to the furcation is within the bone, the more bone loss is required before it becomes exposed.

For mandibular first molars, the average root shaft length is 3 mm on the buccal side and 4 mm on the lingual side. [2] The length of the root shaft of the mandibular second and third molars is the same or slightly longer than that of the first molars, although the roots may be fused.

For maxillary first molars, the average root shaft length is 3-4 mm on the buccal side, 4-5 mm on the mesial side and 5-6 mm on the distal side. [2] As with the mandibular molars, the root shaft length of the maxillary second and third molars is either the same as or slightly longer than that of the first molars, although the roots may be fused.

For maxillary first premolars, bifurcation occurs in 40% of cases, and the average root shaft length is 8 mm both mesially and distally. [2]

Diagnostics

The Nabers probe[5] is used to clinically test for the presence of furcation. Recently, cone beam computer technology (CBCT) has also been used for furcation detection.[6] Periapical and interproximal intraoral radiographs[5] can help in the diagnosis and localization of the bifurcation. The location and extent of the branching should be recorded in the patient's notes.

Only multi-rooted teeth have branching. Therefore, the maxillary first premolar, maxillary and mandibular molars may be involved.

The upper premolars consist of one buccal and one palatal root. Furcation involvement should be checked from the mesial and distal sides of the tooth.

Maxillary molars have three roots: mesiobuccal, distobuccal and palatine. Therefore, check for clefting on the buccal, mesio-palatal and disto-palatal sides.

Mandibular molars have one mesial and one distal root, so check for buccal and lingual involvement.

Care

The goal of treatment is to eliminate bacteria from the exposed surface of the root(s) and define the anatomy of the tooth so that plaque can be better controlled. Patient treatment plans vary depending on local and anatomical factors.

For grade I splitting, scaling and polishing,[6][7] Root surface debridement or furcation grafting can be performed if necessary.

For grade II furcation, furcation repair, open debridement,[6][8] tunnel preparation,[6]root resection,[6] extraction[6] guided tissue regeneration (GTR)[8][6][7] or derivative of the enamel matrix.

Regarding grade III furcation, open debridement,[6][8] tunnel preparation,[6] root resection,[6][7] GTR,[8][6] or tooth extraction[6] can be performed if necessary .

Tooth extraction is usually considered if there is extensive attachment loss or if other treatment options do not provide good results (eg, achieving good gingival contour for good plaque control).

Diagnosis[edit]

The Nabers probe is used to clinically test for the presence of a furcation. [ citation needed

] Recently, computerized cone beam technology (CBCT) has also been used to detect furcation.

[5] Periapical and interproximal intraoral radiographs can help diagnose and locate the bifurcation. [ citation needed

]

Only multi-rooted teeth have branching. Therefore, the maxillary first premolar, maxillary and mandibular molars may be involved. The upper premolars consist of one buccal and one palatal root. Maxillary molars have three roots: mesiobuccal, distobuccal and palatine. Mandibular molars have one mesial and one distal root, etc.

Classification of furcation defects[edit]

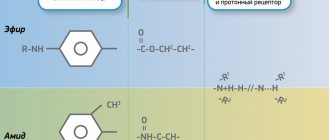

Because of its importance in the assessment of periodontal disease, a number of classification methods have been developed to measure and record the extent of bifurcation involvement; most measures are based on horizontal measurements of attachment loss at the bifurcation.

In 1953, Irving Glickman

divided furcation lesions into the following four classes:[3]

- Grade I

is an initial furcation lesion with an associated periodontal pocket remaining coronal to the alveolar bone. The pocket primarily affects soft tissue. Early bone loss may have occurred, but this is rarely evident radiographically. - Grade II

- There is some horizontal component of bone loss between the roots that results in the area of interest, but there is still enough bone attached to the tooth (at the dome of the furcation) that multiple areas of furcal bone loss, if present, are not associated. - Grade III

- The bone is no longer attached to the fork of the tooth, resulting in a through-tunnel. However, due to the angle in this tunnel, the fork cannot be fully explored; if the combined measurements from different sides are equal to or greater than the width of the tooth, a grade III defect can be assumed. In early grade III lesions, soft tissue may still obstruct the furcation, making detection difficult. - Grade IV

- Essentially a grade III lesion, grade IV describes a penetrating lesion that has undergone sufficient bone loss to make it fully probing.

In 2000, Fedi et al.

modified the Glickman classification to include two grades of grade II furcation defect:[4]

- Grade II, Grade I

- exists when furcal bone loss has a vertical component of >1 to <3. - Grade II, Grade II

—exists when furcal bone loss has a vertical component >3 mm but is still not transmitted through.

In 1975, Sven-Erik Hamp

together with Lind and Sture Nyman classified fork defects according to their depth.

- Class I

- Furcation defect less than 3 mm deep. - Class II

- The furcation defect is at least 3 mm deep (and thus overall greater than half the buccolingual thickness of the tooth) but is not through (i.e. there is still some interradicular bone attached to the corner of the tooth). Thus, the bifurcation defect represents a dead end. - Class III

- Furcation defect spanning the entire width of the tooth such that no bone is attached to the furcation angle. [4]