CLASSIFICATION

Odontogenic infections (infections of the oral cavity), depending on the anatomical location, are divided into truly odontogenic

associated with damage to tooth tissue (caries, pulpitis);

periodontal

, associated with damage to the periodontium (periodontitis) and gums (gingivitis, pericoronitis), surrounding tissues (periosteum, bone, soft tissues of the face and neck, maxillary sinus, lymph nodes);

non-odontogenic

, associated with damage to the mucous membranes (stomatitis) and inflammation of the major salivary glands.

These types of infections can cause serious life-threatening complications from the cranial cavity, retropharyngeal, mediastinal and other localizations, as well as hematogenously disseminated lesions of the heart valve apparatus, sepsis.

Purulent infection of the face and neck

may be of non-odontogenic origin and includes folliculitis, furuncle, carbuncle, lymphadenitis, erysipelas, hematogenous osteomyelitis of the jaws.

Specific infections (actinomycosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, HIV) can also be observed in the maxillofacial area.

MAIN PATIENTS

Infections of the oral cavity are associated with the microflora that is constantly present here. Usually this is a mixed flora, including more than 3-5 microorganisms.

With truly odontogenic

infections, along with facultative bacteria, primarily viridans streptococci, in particular (

S.mutans, S.milleri

), anaerobic flora is released:

Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Fusobacterium

spp.,

Actinomyces

spp.

In case of periodontal infection, five main pathogens are most often isolated: P.gingivalis, P.intermedia, E.corrodens, F.nucleatum, A.actinomycetemcomitans

, less commonly

Capnocytophaga

spp.

Depending on the location and severity of the infection, the patient’s age and concomitant pathology, changes in the microbial spectrum of pathogens are possible. Thus, severe purulent lesions are associated with facultative gram-negative flora ( Enterobacteriaceae

spp.) and

S.aureus

.

In elderly patients and hospitalized patients, Enterobacteriaceae

spp also predominate.

In the conditions of domestic bacteriological laboratories, it is quite difficult to isolate a specific pathogen of a certain odontogenic infection. However, it seems possible to localize pathogens that play a major role in the development of oral infections in supragingival and subgingival plaque.

PRINCIPLES OF TREATMENT OF INFECTIONS OF THE ORAL CAVITY AND MAXILLOFACIAL AREA

Treatment of odontogenic infection

often limited to local therapy, including standard dental procedures.

Systemic antibacterial therapy is carried out only when odontogenic infection spreads beyond the periodontal period (under the periosteum, into the bones, soft tissues of the face and neck), in the presence of elevated body temperature, regional lymphadenitis, and intoxication.

When choosing antimicrobial therapy in a hospital setting, in cases of severe purulent infection, it is necessary to take into account the possibility of the presence of resistant strains among anaerobes such as Prevotella

spp.,

F. nucleatum

to penicillin, which determines the prescription of broad-spectrum drugs, amoxicillin/clavulanate in monotherapy or a combination of fluoroquinolone with metronidazole.

Due to increasing levels of resistance by Streptococcus

spp.

to tetracycline and erythromycin, these drugs can only be used as alternatives. Since metronidazole has moderate activity against anaerobic cocci ( Peptostreptococcus

spp.), simultaneous administration of β-lactam antibiotics is necessary to increase effectiveness.

Preventive systemic use of AMPs when performing dental procedures in the oral cavity or periodontium does not guarantee a reduction in the incidence of infectious complications in somatically healthy patients. Convincing data on the sufficient effectiveness of topical antibiotics for oral infections have not been obtained. At the same time, oral bacteria are a reservoir of determinants of resistance to AMPs. Excessive and unjustified use of antibiotics contributes to their appearance and the development of resistance of pathogenic microflora.

ODONTOGENIC AND PERIODONTAL INFECTION

PULPITIS

Main pathogens

Viridans streptococci ( S. milleri

), non-spore-forming anaerobes:

Peptococcus

spp.,

Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Actinomyces

spp.

Choice of antimicrobials

Antimicrobial therapy is indicated only in case of insufficient effectiveness of dental procedures or spread of infection into surrounding tissues (periodontal, periosteal, etc.).

Drugs of choice

: phenoxymethylpenicillin or penicillin (depending on the severity of the disease).

Alternative drugs

: aminopenicillins (amoxicillin, ampicillin), inhibitor-protected penicillins, cefaclor, clindamycin, erythromycin + metronidazole.

Duration of use

: depending on the severity of the current (at least 5 days).

PERIODONTITIS

Main pathogens

Microflora is rarely detected in the periodontal structure and is usually S.sanguis, S.oralis, Actinomyces

spp.

In periodontitis in adults, gram-negative anaerobes and spirochetes predominate. P.gingivalis, B.forsythus, A.actinomycetemcomitans and T.denticola

are highlighted most often.

In juveniles, there is rapid involvement of bone tissue in the process, with A. actinomycetemcomitans

and

Capnocytophaga

spp.

P.gingivalis

is rarely isolated.

In patients with leukemia and neutropenia after chemotherapy along with A. actinomycetemcomitans

C.micros

is isolated , and in prepubertal age -

Fusobacterium

spp.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: doxycycline; amoxicillin/clavulanate.

Alternative drugs

: spiramycin + metronidazole, cefuroxime axetil, cefaclor + metronidazole.

Duration of therapy

: 5-7 days.

For patients with leukemia or neutropenia after chemotherapy, cefoperazone/sulbactam + aminoglycosides are used; piperacillin/tazobactam or ticarcillin/clavulanate + aminoglycosides; imipenem, meropenem.

Duration of therapy

: depending on the severity of the course, but not less than 10-14 days.

PERIOSTITIS AND OSTEOMYELITIS OF THE JAWS

Main pathogens

With the development of odontogenic periostitis and osteomyelitis, S. aureus

, as well as

Streptococcus

spp., and, as a rule, anaerobic flora prevails:

P.niger, Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Bacteroides

spp.

Specific pathogens are less commonly identified: A.israelii, T.pallidum

.

Traumatic osteomyelitis is often caused by the presence of S.aureus

, as well as

Enterobacteriaceae

spp.,

P.aeruginosa

.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: oxacillin, cefazolin, inhibitor-protected penicillins.

Alternative drugs

: lincosamides, cefuroxime.

When P.aeruginosa

, antipseudomonas drugs (ceftazidime, fluoroquinolones) are used.

Duration of therapy

: at least 4 weeks.

ODONTOGENIC MAXILLARY SINUSITIS

Main pathogens

The causative agents of odontogenic maxillary sinusitis are: non-spore-forming anaerobes - Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Bacteroides

spp., as well as

H.influenzae, S.pneumoniae

, less often

S.intermedius, M.catarrhalis, S.pyogenes

.

Isolation of S.aureus

from the sinus is characteristic of nosocomial sinusitis.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: amoxicillin/clavulanate. For nosocomial infection - vancomycin.

Alternative drugs

: cefuroxime axetil, co-trimoxazole, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol.

Duration of therapy

: 10 days.

PURULENT INFECTION OF SOFT TISSUE OF THE FACE AND NECK

Main pathogens

Purulent odontogenic infection of the soft tissues of the face and neck, tissue of deep fascial spaces is associated with the release of polymicrobial flora: F. nucleatum

, pigmented

Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Actinomyces

spp.,

Streptococcus

spp.

ABSCESSES, PHLEGMONS OF THE FACE AND NECK

Main pathogens

With an abscess in the orbital area in adults, a mixed flora is released: Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Bacteroides

spp.,

Enterobacteriaceae

spp.,

Veillonella

spp.,

Streptococcus

spp.,

Staphylococcus

spp.,

Eikenella

Streptococcus

spp.,

Staphylococcus

. predominate in children .

The causative agents of abscesses and phlegmon of non-odontogenic origin, most often caused by minor skin lesions, are S.aureus, S.pyogenes

.

With putrefactive-necrotic phlegmon of the floor of the mouth, a polymicrobial flora is released, including F.nucleatum, Bacteroides

spp.,

Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Streptococcus

spp.,

Actinomyces

spp.

S.aureus

can be isolated in patients with severe disease (more often in patients suffering from diabetes and alcoholism).

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice:

inhibitor-protected penicillins (amoxicillin/clavulanate, ampicillin/sulbactam), cefoperazone/sulbactam.

When P.aeruginosa

- ceftazidime + aminoglycosides.

Alternative drugs:

penicillin or oxacillin + metronidazole, lincosamides + aminoglycosides of the II-III generation, carbapenems, vancomycin.

Duration of therapy:

at least 10-14 days.

BUCCAL CELLULITE

Main pathogens

Usually observed in children under 3-5 years of age. The main pathogen is H. influenzae

type B and

S. pneumoniae

.

In children under 2 years of age, H. influenzae

is the main pathogen, and bacteremia is usually observed.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: amoxicillin/clavulanate, ampicillin/sulbactam, third generation cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) IV, in high doses.

Alternative drugs

: chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole.

Duration of therapy

: depending on the severity of the current, but not less than 7-10 days.

LYMPHADENITIS OF THE FACE AND NECK

Main pathogens

Regional lymphadenitis in the face and neck is observed with infection in the oral cavity and face. Localization of lymphadenitis in the submandibular region, along the anterior and posterior surfaces of the neck in children aged 1-4 years, is usually associated with a viral infection.

Abscess formation of lymph nodes is usually caused by a bacterial infection. With unilateral lymphadenitis on the lateral surface of the neck in children over 4 years of age, GABHS and S.aureus

.

Anaerobic pathogens, such as Bacteroides

spp.,

Peptococcus

spp.,

Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

F.nucleatum, P.acnes

, can cause the development of odontogenic lymphadenitis or inflammatory diseases of the oral mucosa (gingivitis, stomatitis), cellulite.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice: AMPs corresponding to the etiology of the primary source of infection.

The problem of treating purulent-inflammatory diseases (PIDs) of the face and neck is relevant for both dentists in clinics and maxillofacial surgeons in hospitals. About 50% of people in maxillofacial hospitals, and about 20% who seek help from a dentist and surgeon in polyclinics, are patients with inflammatory diseases of the maxillofacial area (MFA), among them 60–80% of patients with abscesses and phlegmon, the incidence of which has increased 1.5–2.0 times over the last decade [1–3]. There has been a steady increase in atypically and severely progressing phlegmons, spreading simultaneously in several cellular spaces, with the development of such serious complications as sepsis, contact mediastenitis, thrombosis of the cavernous sinus of the dura mater [4–9]. Low-symptomatic “erased” forms of phlegmon occur among 13.4–22% of patients, are characterized by a long course and present difficulties for diagnosis, which contributes to late hospitalization and untimely treatment [10–12]. The microbial etiology of maxillary sinusitis is determined by the localization of the primary process (connection with the oral cavity, teeth) [13, 14].

As a rule, there are associations of 2–6 types of microorganisms: aerobes (streptococci and staphylococci) and obligate anaerobes (bacteroides, fusobacteria, peptococci, peptostreptococci) [15, 16]. The frequency of isolation of anaerobes is up to 52–68%, less often in non-odontogenic processes of the maxillofacial lesion – 20%, in odontogenic processes – 67.7–96% [13, 15–18].

Being in symbiosis, bacteria gradually enter into antagonistic and synergistic relationships during the development of infection. This explains the negative dynamics of the clinical picture of the disease in mixed anaerobic-aerobic infections. For example, it was noted that representatives of the genus Veillonella exhibit weak pathogenicity in monoculture, and the synergistic effect of accompanying aerobic microbes increases the pathogenicity of these bacteria. Purulent-inflammatory processes occurring with the participation of associations consisting of pepto-, peptostreptococci and gram-positive cocci are more severe and more extensive than lesions caused by a monoculture of aerobic gram-positive cocci [19].

The main causative agents of gastrointestinal infections of the maxillofacial area

GVZ of the maxillofacial area and neck, requiring surgical intervention, are often of odontogenic origin and are complications of an infectious process in the oral cavity. The spread of inflammation is possible by contact - through fascial spaces (infection of the floor of the mouth) and hematogenous.

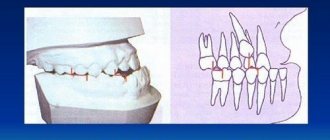

Oral infections are divided into the following types depending on the anatomical location [1]:

- odontogenic, associated with damage to tooth tissue (caries, pulpitis);

- periodontal, including periodontium (periodontitis) and gums (gingivitis, pericoronitis), surrounding soft and bone tissue.

The main causative agents of odontogenic infections are microorganisms that are constantly present in the oral cavity: mainly viridans streptococci (Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus milleri), non-spore-forming anaerobes (Peptostreptococcus spp., Fusobacterium spp., Actinomyces spp.). In case of periodontal infection, five main pathogens are most often identified: Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Eikenellacorrodens, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, and less commonly – Capnocytophaga spp. [20, 21]. Depending on the location and severity of the infection, the patient’s age and concomitant pathology, changes in the microbial spectrum of pathogens are possible.

Thus, severe purulent lesions are associated with facultative gram-negative flora (Enterobacteriaceaeespp.) and Staphylococcusaureus. In patients with diabetes mellitus, elderly people and patients hospitalized in a hospital, Enterobacteriaceae spp. also predominate. [22].

Research by Yu.V. Alekseeva (2005) demonstrated that Staphylococcus spp. is isolated in odontogenic inflammatory diseases. (15%), Streptococcus spp. (6%) and obligate anaerobic bacteria (79%). Anaerobes are represented by gram-positive microorganisms - Bacteroides spp., Fusobacterium spp., gram-positive cocci. In 86%, resident flora is sown, in 7%, pathogenic strains are sown.

In studies by L. Chavez de Paz, G. Svensater, G. Dalen, G. Bergenholtz (2004), it was found that Streptococcus gordonii, Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcusoralis, and Enterococcus spp. were most often isolated from the root canals of teeth with chronic destructive periodontitis. Lactobacillus paracasei.

The development of odontogenic periostitis and osteomyelitis in 50% of cases is caused by S. aureus and Streptococcus spp., but, as a rule, anaerobic flora prevails: Peptococcus niger, Peptostreptococcus spp., Bacteroides spp. [25].

In non-odontogenic osteomyelitis, the key pathogens are methicillin-sensitive staphylococci (MSSA) - 52%, coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) - 14%, methicillin-resistant staphylococci (MRSA) - 2% and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (4.4%) [26]. Traumatic osteomyelitis is often caused by the presence of S. aureus, as well as Enterobacteriaceae spp., P. aeruginosa [27].

The causative agents of odontogenic maxillary sinusitis are non-spore-forming anaerobes - Peptostreptococcus spp., Bacteroidesspp., as well as Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus intermedius, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxellacatarrhalis, Streptococcus pyogenes. Isolation of S. aureus from the sinus is characteristic of nosocomial sinusitis [22].

Purulent odontogenic infection of the soft tissues of the face and neck is associated with the release of polymicrobial flora: Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Peptostreptococcus spp., Bacteroidesspp., F. nucleatum, Enterobacteriaceaespp., Veillonellaspp., Eikenellaspp. The causative agents of abscesses and phlegmon of non-odontogenic origin, most often caused by skin damage, are S. aureus, S. pyogenes. In 50.9% of patients with phlegmon of the face and neck, anaerobic bacteria Peptostreptococcus spp., Bacteroides spp., Veillonellaspp. are isolated; Staphylococcus spp. – in 23.7% of observations, Streptococcus spp. – in 18.6% [28].

For putrefactive-necrotic phlegmon of the face and neck, a polymicrobial flora is isolated, including F. nucleatum, Bacteroidesspp., Peptostreptococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Actinomycesspp. In addition to the microorganisms mentioned above, gram-negative bacteria and S. aureus are often isolated from patients with severe disease [25]. Klebsiella spp., Enterococcus spp., S. aureus, P. aeruginosa play an important role in patients with diabetes mellitus, and the presence of P. aeruginosa is associated with the most unfavorable prognosis [29, 30].

When lymphadenitis of the face and neck develops, group A β-hemolytic streptococcus and S. aureus are isolated in 70–80% of cases. Anaerobic pathogens, such as Bacteroides spp., Peptostreptococcus spp., Peptococcus spp., F. nucleatum, Propionibacterium acnes, can cause the development of odontogenic lymphadenitis [22].

Principles of empirical antibacterial therapy (ABT) and features of the use of antibiotics in dentistry

Treatment of patients with maxillofacial infarction is complex and includes surgery, local treatment of a purulent wound, systemic ABT, physical therapy, and, if indicated, detoxification and immunocorrective therapy. The tactics of surgical treatment have now been defined quite fully. It includes the opening of a purulent-inflammatory focus by layer-by-layer dissection of the tissue above it, as well as drainage of the surgical wound in order to create conditions for the evacuation of purulent exudate containing pathogens, their metabolic products and tissue breakdown [3, 31].

According to Medical Advertising News (USA), dentists prescribe from 2 to 10 antibiotics daily, antibiotics are especially often used by patients with complaints of pain and swelling of the soft tissues of the face [32]. There is virtually no data confirming the advisability of systemic ABT for many procedures in dentistry. Moreover, the results of randomized clinical trials indicate the undesirability of systemic use of antibiotics in outpatient practice [33]. The oral cavity, in a figurative expression, is the “cradle of resistance”, since it abounds in flora, the etiological significance of which in the development of the source of infection is often not identified, and inadequate use of antimicrobial drugs changes the qualitative response of not only clinically significant pathogens, but also representatives of obligate, as well as facultative flora. ABT is often carried out in a hospital without bacteriological control, which contributes to the development of microflora resistance, allergization of the body, and disruption of intestinal microbiocenosis [34, 8, 35].

In the clinic of surgical dentistry, antibiotics are used for intravenous lesions of the maxillofacial area and for the purpose of prevention (for injuries of soft tissues and bones of the face, after implantation, reconstructive operations, systemic prophylaxis with artificial heart valves) [33].

When planning empirical ABT, it is necessary to focus on individual fluctuations in the qualitative and quantitative composition of the oral microflora, which depend on age, diet, hygiene skills, and the presence of pathological processes in the teeth and gums. The rational choice of antibiotics is facilitated by the use of rapid methods for determining the sensitivity of identified pathogens to them, focusing on the most clinically significant of these drugs, and assessing the organoleptic properties of wound exudate [36, 37]. When thick, creamy pus is obtained from the lesion, it can be assumed that the causative agent is staphylococcal flora; when receiving liquid, foul-smelling pus - a microbial association with a predominance of gram-negative bacillary flora. If pus is not obtained from the wound, but a cloudy-reddish liquid is released, the presence of anaerobic microflora can be assumed [22].

When planning treatment in a dental clinic, it is advisable to focus on oral antibiotics with high bioavailability, a long half-life, and minimal impact on the intestinal microflora [38]. When treating a patient in a hospital setting, it is advisable to choose a drug that has forms for parenteral and oral administration for the purpose of stepwise therapy [39].

At the outpatient stage, ABT is carried out for acute and exacerbations of chronic periodontitis, acute periostitis, purulent-inflammatory diseases of the soft tissues of the maxillofacial area, i.e. processes that tend to spread. For prophylactic purposes, antibiotics are used during surgical interventions (removal of impacted and dystopic teeth, cystectomy, tooth-preserving operations, implantation) [40].

The main reasons for the ineffectiveness of ABT may be:

- undrained focus of purulent inflammation or the presence of a foreign body in the wound;

- non-bacterial pathogen of an infectious process (viruses, fungi);

- inadequate choice of antibiotic (the pathogen is naturally resistant);

- changes in the sensitivity of the pathogen during treatment;

- use of subtherapeutic doses of the drug, violation of the method of administration or administration technique (violation of instructions for dilution and storage);

- purulent-inflammatory processes of the maxillofacial area are a complication of the underlying disease (congenital cysts, neoplasms);

- superinfection with hospital microflora.

Antibacterial drugs recommended for the treatment of patients with gastrointestinal tract infections of the face and neck are presented in the relevant regulatory documents of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation. When treating abscesses, boils, carbuncles of the soft tissues of the maxillofacial area, cephalosporins (cefuroxime) or macrolides (erythromycin) are recommended - order No. 126 of 02/11/2005, for phlegmons - cefuroxime, amoxicillin/clavulanate, spiramycin, levofloxacin - order No. 477 of 07/29/2005, for osteomyelitis - pefloxacin, levofloxacin, ceftazidime, cefuroxime, imipenem, rifampicin, ceftriaxone - order No. 520 of 08/11/2005.

Currently, we do not have fundamental recommendations for ABT for intravenous thromboembolism. At the same time, the resistance status of oral microflora (S. aureus, S. pyogenes, viridans streptococci, gram-negative microorganisms and even Candida fungi) has changed significantly. Among the initially present resistant strains, during selection, associated polyresistance to the most commonly used antibiotics (macrolides, penicillins) appeared. Of particular concern are cases of nosocomial infection of the maxillofacial area, accompanied by a systemic inflammatory response, spread of the process to vital areas (mediastinum, cranial cavity), and unfavorable outcome. Vancomycin and linezolid should be used in initial therapy if there is a risk of isolating MRSA strains, and risk factors for isolating extended-spectrum β-lactamase producers (Enterobacteriaceae spp.) are the basis for prescribing carbapenems. The prospects for the optimal choice of antimicrobial drug for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, unfortunately, are not clear today.

In clinical practice, dental surgeons widely use antibiotics for prophylactic purposes in the treatment of facial bone fractures. There is evidence of the advisability of prophylaxis during primary surgical treatment, however, continuing the course of ABT after repositioning of fragments does not reduce the overall incidence of infectious complications [41].

.The main pathogens of HVO of the maxillofacial area.

Dental manipulations in the oral cavity can lead to hematogenous spread of microorganisms (or their metabolic products, or immune complexes) with the development of distant sites of infection [42]. The questions of when and under what circumstances antibiotic prophylaxis is required for diseases of the maxillofacial area remain controversial [43].

Thus, rational ABT and antibiotic prophylaxis in dental practice are one of the mechanisms regulating the state of resistance in general. Limiting the systemic use of antibiotics in outpatient dentistry, reducing ABT courses and de-escalation therapy with adequately selected antimicrobial drugs for severe and nosocomial infections of the maxillofacial area is the main way to improve the quality of care for patients with intravenous infections of the maxillofacial area and neck.

Information about the authors: Kovaleva Natalya Sergeevna – assistant at the Department of Surgical Dentistry, SGMA; Antonina Petrovna Zuzova – Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, SSMA. Email

NON-ODONTOGENIC AND SPECIFIC INFECTION

NECROTIC STOMATITIS (VINCINS ULCER-NECROTIC GINGIVOSTOMATITIS)

Main pathogens

Fusobacterium is concentrated in the gingival sulcus

, pigmented

Bacteroides

, anaerobic spirochetes. With necrotizing stomatitis, there is a tendency for infection to quickly spread into surrounding tissues.

The causative agents are F. nucleatum, T. vinsentii, P. melaninogenica, P. gingivalis and P. intermedia

.

In patients with AIDS, C. rectus

.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice:

phenoxymethylpenicillin, penicillin.

Alternative drugs:

macrolide + metronidazole.

Duration of therapy:

depending on the severity of the current.

ACTINOMYCOSIS

Main pathogens

The main causative agent of actinomycosis is A.israelii

, association with gram-negative bacteria

A. actinomycetemcomitans

and

H. aphrophilus

, which are resistant to penicillin but sensitive to tetracyclines, is also possible.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: penicillin at a dose of 18-24 million units/day, with positive dynamics - transition to step-down therapy (phenoxymethylpenicillin 2 g/day or amoxicillin 3-4 g/day).

Alternative drugs

: doxycycline 0.2 g/day, oral drugs - tetracycline 3 g/day, erythromycin 2 g/day.

Duration of therapy

: penicillin 3-6 weeks IV, drugs for oral administration - 6-12 months.

Treatment of inflammatory diseases in Kaluga

If any symptoms of the above diseases occur, it is important to consult a doctor immediately. Even a day of delay can result in serious complications. An oral and maxillofacial surgeon working in our clinic will conduct a thorough examination and prescribe competent treatment. Make an appointment by phone or through the feedback form on the website.

We are always happy to help you and invite you to medical assistance! Be alert! You can make an appointment by phone; 8 (4842) 27-72-50.